BETAS

Or: League of Extraordinary Gentlefolk

Let's end the year with a bang and make plans for The

Writing Career in 2013. If you're prone to procrastination or writer's block, I

highly encourage you to get your ass in a chair and hammer out a writing plan

for 2013 in the form of New Year's Resolutions.

It's going to be an action plan of ten things. An action

plan that will benefit you, and get you moving at a solid pace, will have realistic and measurable goals.

If you're a newbie writer, among the top five of those goals

should be to acquire a Beta. And the goal after that should be to become a Beta yourself.

|

| Adding an extra T to Beta gets you Betta fish. |

Let's get on the same page about what a Beta is and why you

need one, then I'll list some qualities to look for. (If you know what a Beta

is, you can skip to Guidelines.)

The term Beta Reader refers to a person who reads your WIP after you've written it, before you've submitted it to agents,

publishing houses, or indie-pubbed it in eformat.

Wikipedia says the

term Beta Reader was appropriated by the writing world from the programming world.

After a computer program is conceived and created, it goes to Beta users, whose aim is to find flaws with

the program before it goes to market.

Beta Readers do the same thing: find flaws in your WIP

before the public sees it. And don't get all uppity and defensive, thinking

your WIP is flawless. It's not. I guarantee it's not. Because writing with an

eye on spelling, correct grammar, clichés, dialogue tags, etc. is a slow and

crippling way to write. That's why I frame these posts as if you've already written

your story, and you're in 1st through nth revision, and not information you should necessarily

have in your head while you're

describing a messy evisceration.

When your WIP is done and you've revised it yourself once or

numerous times, you might know it too well. You know why Adam ran away from home. You know what the inside of that magic castle looks like. All that is

in your head.

A Beta can tell you if you've been successful painting scenes in your reader's head.

To bring it back to the programming analogy, a Beta Reader

will test your WIP for flaws that garble

your message.

Those flaws could include:

- A horrendous plot hole: If they have flying carpets, why couldn't they fly over the Forest of Epic Evil instead of going through it?

- Character inconsistencies: Old Man Barley used to be really nice to Jack. How come in Chapter 18, he's a total dick?

- Detail inconsistencies: If he broke his leg while fighting Jorba the Giant Pimp, how is he sprinting down Lombard Street?

- And a myriad of other flaws ranging from simple typos to story structure.

Can one Beta do all these things? The truth is no. I

guarantee that as well. Reading is subjective

and every person will have a different set of cultural values, writing experience, professional expertise. So while you can

have a Beta that does a lot of

flaw-finding, keep in mind that what one Beta might consider a "flaw"

could be another Beta's "ground-breaking experimental structure by the

literary genius of our time."

There are Betas who will read through an entire WIP and

offer just a few but critical notes on each chapter. Some may hand back a

hardcopy with so much red ink, it looks like they used it to staunch blood flow

from a gut wound. How do you know which type you're getting?

Ask.

Guidelines for choosing a Beta:

Know your Beta. This isn't about trusting them with you and

your muse's love child. This is about understanding your Beta's talents and

limits. Asking these questions up front can lead to an easier relationship down

the road.

A. Do you want to know what I (the writer) need from you, or

do you prefer a cold read? Some Betas prefer having a bulleted list of what

they should look for: plot holes, believability of sex scenes, slow pace, etc.

Others don't want this information and prefer to find issues on their own (if

there even is an issue with something to begin with!).

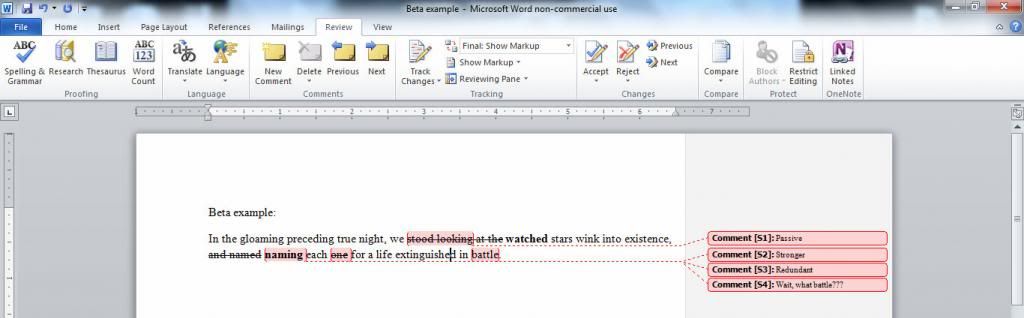

B. How do you prefer making notes? Some Betas do Line-By-Line (LBL) notes. Those look like this:

In the gloaming preceding true night, we stood looking at

the watched stars wink into

existence, and named naming each

one for a life extinguished in battle.

Other Betas prefer to use "New Comment" on MS

Word, which allows them to explain why they suggest changes. Like:

|

| Click to embiggen. |

Some prefer to work with only hardcopy, or only digital

copies, only a few pages or chapters at a time or the whole book at once. Some

are flexible in how they make notes, some won't work with you unless you do

things their way.

Ask about this. Know what method helps you and your story best.

I prefer making notes to explain why I suggest a change. I've

worked with some people who have gotten used to my shorthand: M > TSTL Ch8. *triangle

symbol* (In chapter 8, your protag becomes too

stupid to live because__,

change __.); CAF (Cut this, dip it

in Acid, and burn it in Fire.). Shorthand for things I enjoyed:

AWESOME and ROFLMAO.

C. Do you read my genre? This seems like a no-brainer, but

you'd be surprised how often not

asking this can lead to issues down the road. Each genre has specific elements

which identify it as appropriate for certain readers. At its simplest, a

"genre" will be the location in the bookstore or category in Amazon

or Smashwords where your story can be found by people looking for that flavor.

If you pick a Beta who hasn't read your genre or doesn't

read it enough, they may question why

your focus seems to be on the romance blooming between Peter and Prescott, when

obvi they should be focused on X, Y, or Z instead.

Or they'll look for elements they're familiar with and

lament the fact that there's actually no dragons in the entire story.

Does this mean you must pigeonhole yourself into

genre-specific Betas? Absolutely not. Take what help you can get but be

conscious of their background and apply your knowledge to what they make

comments about.

A reader of historical fiction may question the evolution of

magic in your world, which could mean that something rings false and you need

to include more worldbuilding elements. A Beta who reads mostly YA may ask why

your younger characters talk and act like adults. A Beta who reads mysteries

may point out that a lot of your details seem purposely misleading.

In other words, your story – your message – is being

garbled. Address the issue by showing more truth of your story's world.

D. How quickly do you work? Betas are real people with lives

that may or may not hold writing in the same priority as you do. Waiting can

feel like gouging your eyes out slowly with a rusty melon baller. Better to get

a timeframe in place at the beginning than to have a sad surprise months down

the road.

For example, is it part of your ten New Year's Writing Resolutions

to have your WIP read and revised by June so you can start querying that month?

Or do you plan on publishing independently sometime before school starts,

before your family reunion, as a gift for an anniversary, as a book to mark a

personal milestone? Communicate this.

And listen to what your prospective Beta says about their

personal timeline. Perhaps they're a student. Perhaps they have their own WIP's

to work on too. Perhaps they're juggling multiple Beta projects. Consider what

they say and see if it works for you.

A good Beta can give you a finish time. A great Beta will

deliver as promised.

Faster is not always better (LBLs take me about an hour per

1k words.). Slower doesn't always mean more thorough. It could be there are big

issues that require repeated looks.

E. Is there anything I can do for you in return? Of the

utmost importance, this question. Betas usually don't get paid in money. (When

people I Beta for insist, I refer them to crowdfunding projects on the right

side of my blog.) There are precious few solid rules I write about in my blog.

This is one of them: When you find a Beta, ask this question. Most are also

writers and reciprocity is appreciated. Beta for their WIP in return either

while they work on yours, or for a future project.

A good Beta will help your current story. A great Beta will help your writing career. Their comments and critiques should challenge you. Swap samples first. If most of their comments make you feel like your story is bulletproof, you might need a Beta with more experience.

Some caveats on Beta relationships:

1. A Beta is not your WIP's housekeeper; do not expect them

to fix your mistakes. It is your

responsibility as a writer to have a firm grasp on your craft's tools.

This includes knowledge of:

Grammar

Punctuation

Manuscript format for your chosen method of publication

Spelling

Genre elements

Betas should receive a WIP that is as close to perfect as

you can make it so they can find the flaws you

couldn't catch.

2. Respect each other's boundaries; Betas will not rewrite

scenes, chapters, your entire book for you, nor should you expect that of them.

3. If a friend asks to Beta for you, understand that it can

have an impact on your friendship. I had a friend ask to Beta for me once, and

I gave him the WIP. He made it to Chapter 5, I think, and offered just a few

comments. Interested in what he had to say about the rest of the story, I kept

waiting for him to finish it. How many times can you ask if they're done before

they get annoyed? Not to mention the mind games you play on yourself: are they

not reading it anymore? Did they think it sucked and they're trying to spare my

feelings?

Turns out that story was too dark for him… and had no sex

scenes.

If you have a friend who is genuinely interested and has

some writing background, go for it. Or if your WIP has technical or historical

aspects you'd like to run by someone who has experience in that field, awesome.

Otherwise, try not to give in to the temptation of taking advantage of a friend

who asks to Beta unless your friendship can take the strain.

Yes, it will be strained. Writing reveals things that you

may not want close friends or family members to know. Heck, it can reveal

things about the reader too. I once pitched a story idea to two dozen friends.

The story dealt with issues of faith versus obligation to one's community. My

friends were split down the middle as to who preferred what I considered to be

the selfish option versus the option of sacrifice. Holy sh*t, was it an eye

opener.

4. A Beta is not your marketing tool. Their comments should

not be used to get other Betas or future readers. If they liked something about

your WIP, bask in the praise, keep that section as is, and use it to motivate

you. If the Beta finds a flaw or suggests a change, reflect on their comment

and either implement or ignore. A comment advertised out of context can make

you or your Beta look bad.

5. Be honest and curious, not defensive. You can scream

"So and so doesn't know what he/she's talking about!" to your dog as

long and often as you want, but it's unprofessional to do so to the Beta,

especially in public. Betas work for free, remember? And whatever the critique,

there was a reason for it. If you don't see it or disagree, for f*ck's sake,

ask.

One step further: A good Beta will tell you why they have

that critique. A great Beta will listen to you explain yourself and may even

offer suggestions on how to achieve what you were trying to do.

6. Thank them, often and honestly. And if it seems like all

their comments are things that need work, ask them what they liked about the

story! And ask them if they'd like to be thanked in your book before doing it.

Lastly, be a Beta Reader yourself. This goes beyond the reason

of reciprocity I listed above.

Beta Reading offers the following advantages:

* Even if you've never taken a Creative Writing course, you

have read many books. You know what works. Reading someone's unpolished (or

even heavily revised) WIP can show you what doesn't work so you can avoid those issues in your own writing.

* A different story, written from a different POV or with a

different Voice, can reset your mind and help you see your own story through

fresh eyes.

* It will help your reading skills – perhaps to an extent

you regret. (I critique almost everything I read now – even Twitter blurbs!

Argh!) It bleeds into your life. Spotting

and pointing out "Show, don't Tell" makes group presentations pop.

Asking for "More Details" helps you see the world more vividly. Noting

"Pacing" issues, however, has ruined many movies for me.

Do you absolutely positively need a Beta Reader? It depends

on who you ask. I'll offer a final example.

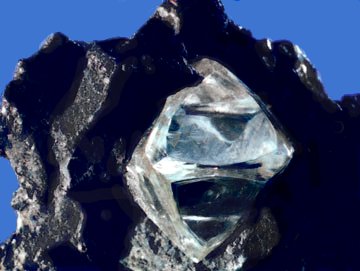

|

| This is a diamond. No, really. |

Writers sometimes tell me that

their early drafts seem wonderful one moment, horrible the next. To which I

reply that all early drafts are as ugly as new diamonds (they look like quartz,

don't they?). When you first wrest the story from the chaos and darkness of your mind,

it's flawed and dirty. Only after you've cleaned it up and chiseled it into

shape can you see the true beauty hiding within.

Lots of people can find gems, given the motivation and

opportunity. But it's the work afterwards that yields the best results.

Lots of people can write a story. The execution, the

writing, is what can make your story stand out. In other words: How clear was

your message? How transparent was the boundary between your world and mine?

A Beta Reader might have the skills and tools you haven't

acquired yet. They might better see what to cut, and what to leave alone.

So in the end, perhaps the question you can ask is not

whether or not you need a Beta Reader, but where to find one.

Here ya go:

Absolute Write Forum: Build relationships here.

Writing Groups in your area.

Happy New Year!

J

Coming up in 2013!

Show vs. Tell

Jay Groce

Passive

Characterization

Dialogue Tags

Verbing

Robert Bevan

No comments:

Post a Comment